A cocoa plantation in the heart of the Peruvian Amazon

We are in the upper Amazon basin, the botanical cradle of cocoa. In this area, humans and animals consumed cocoa in one way or another 5000 years before we bought our first Fair Trade chocolate bar.

But how did we end up here? My mother is from Shapaja, a small village of fishermen and farmers by the river. My parents decided to return to these lush lands in 2012 to cultivate organic cocoa. They now live in a garden of Eden on the left bank of the Huallaga.

My father loves to remind us that Werner Herzog filmed Aguirre, the Wrath of God just down from the plantation! A hallucinatory film about 16th-century conquistadors losing their minds in search of El Dorado. We think we’ve found it!

Early in the morning the mist still envelops the surrounding forest, we follow my father, cap on his head and machete in hand, through the plantation. They named the place Wasi-Manta, ‘of the house’ in Quechua. It’s a family farm of about ten hectares, where 10,000 cocoa trees are alongside various species of trees, multicolored birds, micro-monkeys, and snakes!

We put on sturdy Quechua shoes and recycle Quentin’s shirts to make an insect-proof uniform. We always have to more or less watch where we put our hands, as isulas – giant Amazon ants, spiders, and vipers are also part of the game.

In the late 1990s, cocoa cultivation supplanted coca, a tonic plant whose leaves are used for therapeutic purposes by locals and turned into white powder by narcos.

The authorities, in collaboration with the American DEA, had the bright idea to promote an economic alternative to coca to small farmers with the CCN – a cloned cocoa. This one has a high yield, but its flavors are poor. The balance is fragile because cocoa can sometimes be less profitable than coca!

At Wasi Manta we take the opposite approach by cultivating exclusively organic criollo, a rarer and more fragrant variety, but less in a hurry to grow!

From the cocoa tree to the cocoa bean

Under the canopy, the shade, the black earth and the rain

To start with, the earth. To grow well, cocoa needs organic soil, with lots of nutrients! Five million years ago, the Pebas Sea covered the upper Amazon basin, hence the richness of the soils and subsoils in this land.

It is called “black earth”. Many leaves, sometimes fruits, cover the ground, this organic matter acts as a natural fertilizer.

Here the plantation is on a slope, at an altitude varying from 200 to 700 meters. This allows for good drainage of the ground, ideal for nourishing the cocoa tree roots!

Another essential element: rain. We are in a rainforest, where it rains very regularly. Cocoa needs a heavy rain to grow, at least once a week.

It is dark under the cocoa trees. Other trees, much taller, surround them, nourish them, and protect them, forming a canopy. It’s called agroforestry.

At Wasi-Manta these are mainly citrus trees, orange trees, lemon trees, grapefruit trees, but also banana and papaya trees. All these trees contribute to giving cocoa its fruity aroma.

The baby cocoa

Cocoa trees can be wild, but to develop a plantation, we have to plant small seedlings. These are regularly watered, before becoming fruit-bearing trees 2 to 5 years later – patience is a virtue with criollo!

The flowers blooming on the bark

Pretty cream-colored flowers grow directly on the trunk. Some, finally 1 in 1000, are fertilized and become pods.

We see other things growing on the trunk, ‘chupones’. These are young cocoa shoots that grow directly on the cocoa tree and compete with the reproductive part. They need to be removed daily!

Nevertheless, they can also be used to reproduce cocoa: one is left to grow on the original tree, and when it dies, only the chupon is kept, and so on.

The magic of the pods

It is the mythical fruit of cocoa, stamped on all tablets that claim to be organic or natural, and often used to promote quality cocoa.

Red, green, yellow according to the variety, they color the cacao trees and already foretell the quality of the beans and ultimately the chocolate. From cacao flowers, they grow right on the trunk, sometimes completely vertically, defying the laws of gravity.

But the pods never fall off by themselves!

Right now in the region, there’s a fungus, moniliasis, that’s attacking the pods. It happens when it’s too humid. We then have to remove all the damaged pods to prevent contaminating the trees and quickly pick the ripe pods. It can be disastrous for producers. Some of our neighbors have given up :(.

Harvesting the treasure

Daisio and Mateo are the guardians of the plantation. They also proceed with harvesting the ripe pods and maintaining the cacao trees. They are always escorted by dogs, who spend most of their time rolling in the leaves.

Beyond its appearance, to know if a pod is good, you shake it. If you hear something moving inside, you’re good!

The harvest starts in April and lasts until the beginning of the following year. So, there is cocoa all year round – but a bit less from December. The pods we harvest are about 5 months old. If we wait too long, the beans germinate in the pod and it’s a disaster!

The largest pods grow on the trunk and the large branches. They are also the best because they are supercharged! We harvest them with a machete, scissors, and a pruner. Then we put them in jute bags and gather them on the paths of the plantation.

Majambo, the white cousin of cacao!

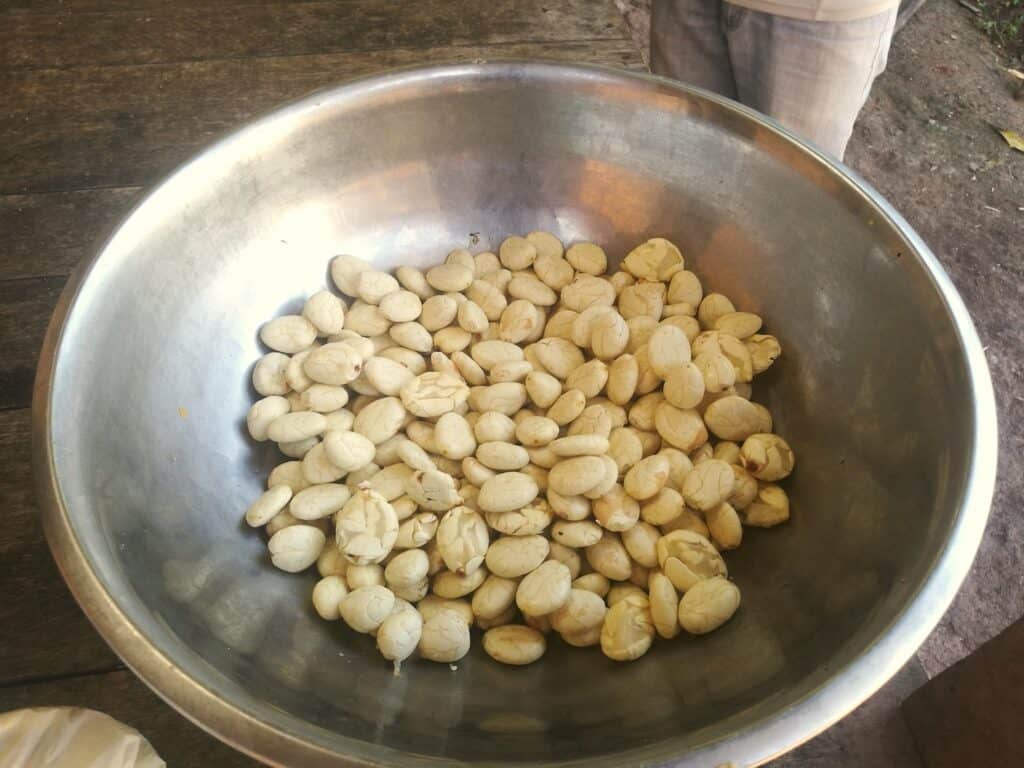

During our visit, we discovered the cousin of cacao, Majambo (Theobroma bicolor). Its pod is much larger and ovoid, and contains white, flat beans that taste like almonds. Chocolate makers in the region use it to make delicious spreads and bars. For us, it’s the future of white chocolate!

Pod splitting with a machete

At the end of the harvesting day, we split open the pods with a machete: it’s called pod splitting. A white substance, mucilage, surrounds the beans. There are between 20 and 50 beans per pod! They cling to the center of the pod, which is called the placenta.

In the pod, you also find a sweet and tangy juice, with a grapefruit taste. It’s a feature of Amazonian pods. Historically here, we harvested cacao for its pulp and mucilage. Monkeys love it!

We carefully shell them and sort them, keeping only those that are good for fermentation. Then at night, we drain them in nets to remove the excess juice they contain.

Fermentation in banana leaves

Fermentation is one of the most delicate steps. It serves to stop the germination of the beans and reveal their precious aromas and nutrients.

We place the beans in natural wooden boxes lined with banana leaves with which they are completely covered. The temperature rises to 43°C and the operation lasts about a week.

A strange smell emanates from it. It’s a sign of quality! In high-quality chocolate making, beans are selected based on their percentage of fermentation. Out of 100 beans, 98 must be properly fermented.

Sun drying

When fermentation is complete, we dry the beans in the sun, on elevated dryers. It’s still the best way to preserve their aromatic qualities and keep them clean. When they are well-dried – after several days, and we judge their storage ability to be optimal, we do a final sorting.

And there you have it, the beans are ready to be marketed! We place them in jute bags and bring them to our buyers in Tarapoto, the largest city in the San Martin region, or in Lima.

We also keep some for chocolate makers who do bean-to-bar, meaning they work the cacao bean themselves to make it into chocolate. But that’s another story! We’ll tell you more soon 😉

Charlotte & Quentin