Louise Browaeys works with both land and words. At the end of this year, she releases three landmark books, The Planetary Health Diet, a Little Punk Cooking Manual and an eco-feminist fable, The Dislocation. Discussion around topics dear to us: food, ecology, and feminism.

You are an author, permaculturist, agricultural engineer, CSR expert… You seem to be engaged in many fields and passionate about different areas, can you tell us about your journey?

I was born near Nantes by the Loire, where my parents are nurserymen. So, I was immediately immersed in the world of plants! I grew up between a garden and a library, and my parents passed on to me this love for gardening and nature.

J’ai fait des études d’agronomie [ à l’AgroParis tech ] et j’ai d’abord travaillé dans l’agriculture biologique. J’ai ensuite découvert le monde des organisations et j’ai travaillé dans la RSE pendant des années. J’ai fait le lien entre une approche “organique” de l’agriculture, et une approche “organique” des organisations, à travers la permaculture humaine en particulier.

I have been self-employed for three years now, and I work on what I call the three ecologies: inner ecology, relational ecology, environmental ecology.

Are you the one who theorized these three ecologies?

Not really, many people claim this today! It originally comes from the philosopher Félix Guattari. Inner ecology refers to discernment and singularity, relational ecology concerns our connection to others, and environmental ecology is the impact we have on the landscape.

I started writing at the age of 12, and I knew that writing would also be something important in my life. I first published essays on permaculture and ecology. Then I wrote recipe books.

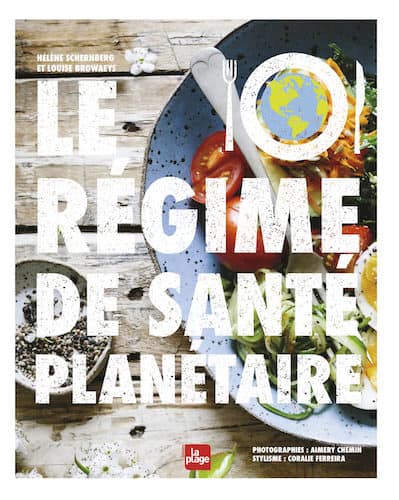

You have just published a book co-authored with Hélène Schernberg, The Planetary Health Diet by La Plage editions. You recommend changing the content of our plates for our health and the environment by 2050. Can you tell us more?

For The Planetary Health Diet, we started from a scientific study called the EAT-Lancet Report, which explains what we need to eat from now on for our health and the planet’s. The link between the two is quite easy to grasp! The foreword is by Walter Willet, an American doctor and nutrition researcher at Harvard University.

We really dissected this study! The idea was to translate a scientific and serious statement into recipes, actions, and new postures. We talked about food transition, provided figures, recommendations…

Increasing the share of plant-based proteins on our plates is fundamental. But we should also reconsider our fats, develop raw, fermented, and diverse contents in our plates.

I have two main preoccupations. The first is pleasure. “Pleasure is a form of production” says Bill Mollison, one of the founders of permaculture. For me, pleasure in cooking is also very important. The second is accepting failures. In the book, we propose very easy recipes to make. Seeing people on Instagram succeed every time can be discouraging. This is indeed a change of mindset, which concerns inner ecology.

This book, Hélène Schernberg and I are very proud of it because we put a lot of work into it. Along with I Cook Eco by Larousse editions, these are the two recipe books I’m happiest with!

What are the key recommendations of the planetary health diet?

I try not to phrase things negatively. Regarding meat: there are many negative injunctions, so we must be careful. The recommendations are the titles of our chapters:

- Consume more fruits and vegetables

- Reduce meat and fish and be more selective

- Rediscover whole grains, consume more legumes, more nuts

- Substitute added eggs

- Reduce milk and dairy product consumption

- Eliminate added sugars, choose fats and processed products wisely

- Favor local and seasonal products

- Prioritize sustainable production methods

- Reduce waste and cooking waste (reuse leftovers, eat tops..).

We also presented the top 15 healthy foods and the top 50 foods of tomorrow. For these foods of tomorrow, we started from another particularly interesting study by WWF and Knorr, which selected those with a lower ecological impact, good nutritional characteristics, accessibility, taste, and acceptance by consumers.

What are the current barriers to this planetary diet?

It’s knowledge! People associate plant-based cooking with boring and not very good food, because they don’t know it. What do you do with a packet of lentils? For me, that’s the barrier. Because when you know how to cook it, Indian-style, Italian-style, or Middle-East-style, with good oils, spices, herbs, colors, it’s very good. There’s a lack of knowledge on how to cook vegetarian so that it’s both appetizing, tasty, and healthy.

When we talk about a “planetary” diet, are we addressing European populations, or is it something that can be applied worldwide?

We tried to be broad when we talk about objectives. These are recommendations that can be generalized. We mostly talk about products from our regions, but all the main themes I just covered can be transposed to highly industrialized countries, where junk food reigns supreme.

In some less industrialized countries, reducing meat consumption doesn’t make sense for certain populations because they don’t eat that much of it already. It’s always necessary to consider soil and climate conditions, cultures, customs, needs, resources… These recommendations should be adaptable to each country. The book targets a European context.

Local agriculture is often associated with ecological agriculture. We discussed this return to locality with Bastien Beaufort, the director of Guayapi (a brand that promotes wild harvest foods from analogous forests in Amazonia and Sri Lanka). According to him, you can also have an ecological diet with foods coming from afar, provided their production method allows for carbon sequestration, compensates for the transport, and collaborates with small producers.

I wouldn’t dare judge a project I don’t know. Yes, we shouldn’t cut ourselves off from some foods that come from afar and cannot be produced here.

Obviously, there are foods that come from afar that are priorities: coffee, cocoa, spices… Since we can’t grow them here, we have to work particularly on these sectors to make them fair.

But buying kiwis from New Zealand when we have them in France seems absurd. Regarding quinoa, there are places where it’s grown and sold fairly, but there are also places where there are significant deviations, destabilizing soils and local economies because suddenly it becomes an export crop, and locals abandon their subsistence farming. This is explained by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart in Histoire des agricultures du monde, a very beautiful book!

Returning to quinoa, we grow it in France, in the Anjou region. I believe I prefer consuming local quinoa rather than quinoa that comes from afar. It’s interesting to taste, to try new foods… But not for some mass-produced products. I’m thinking of bananas, for example, the pollution it creates on-site and the transport it involves.

We talk a lot about super foods, but they don’t necessarily come from afar! I remember studying blackcurrant, prunes, all the super foods we have here in nutrition! We could do without chocolate, but then we would directly affect the principle of pleasure in cooking!

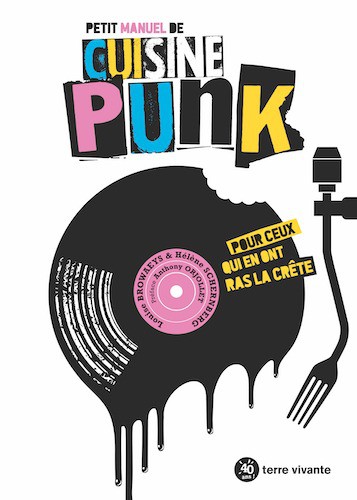

In the Planetary Health Diet, you propose concrete applications with plenty of recipe ideas. You have already published around fifteen recipe books, including one that has just been released on Punk Cuisine with Terre Vivante editions. What is Punk Cuisine?

Regarding this Little Punk Cuisine Manual: it was about taking a new angle to talk about alternative cuisine again, more plant-based, more fair, more healthy…

One might think punk cuisine is about eating beer and kibbles, but no, it’s about returning to the Punk culture. This means advocating for alternative cuisine, and no longer adhering to the somewhat “feminine,” “Instagrammable” side. We talked about anti-capitalist foods, raw, rotten…

There is a scientific article on Punk cuisine, which talks about raw and rotten, meaning raw and fermented. There are different aspects: rejecting consumerism, agro-industry domination, brands, upcycling, respecting the planet, celebrating diversity, saving money…

There is a certain beauty in all that. And also a very quirky side: for example, when you ferment your oat yogurts on the radiator.

And what role does cooking play in your life? Who introduced you to it?

It was my mom. There are family recipes in my books! I’ve always loved cooking, I wrote everything down in my recipe book: recipes from my mother, recipes from my grandmother who I never met, from my great aunt, from my paternal grandmother, recipes from my first boyfriend’s mom…

All this female influence remained, it was done a lot by women. But all of this is changing, more and more men are cooking. Besides, I also have recipes from my grandfather and his famous rice pudding!

That’s what’s good about your books, they’re not too gendered…

No, it’s true that I find that unbearable. For my part I have many activities, I have a child, I don’t want to spend even an hour a day cooking.

What I propose and talk about is easy cooking, that you prepare the day before, or you use leftovers to make something very quickly, very well, very good! I don’t want to spend the whole day on it!

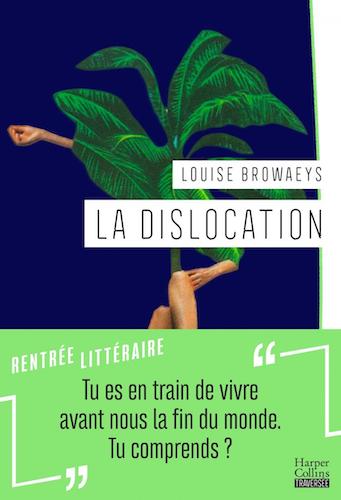

You are also launching a debut novel with Harper Collins this fall, La dislocation, described as an “eco-feminist fable.” How do you see these two challenges, ecology and feminism, being connected?

It’s a broad and delicate question. There are multiple eco-feminisms and a variety of ways to be an eco-feminist. It’s quite difficult to talk about it like this, theoretically.

Let’s say it’s about bringing together these two struggles, ecology and feminism, by drawing a parallel between the oppression women have endured through the ages, and the oppression and violence inflicted on the planet and the earth.

There is the absolutely fascinating thought of Françoise D’Eaubonne, who is a French philosopher we have almost forgotten. She says that all of this began in the Neolithic, when men took control of both the fertility of the soil and the fecundity of women. It is from this point that we enter ten thousand years of capitalism, dominations, appropriations, violence.

Ce qui m’intéresse aussi, c’est le concept de “réappropriation”, avec le mouvement Reclaim aux Etats-Unis par exemple, dont parle notamment Emilie Hache dans son recueil de textes éco-féministes qui porte ce nom là [ Reclaim ]. Comment aujourd’hui les femmes se réapproprient le féminisme et la façon d’être femme ? Elle disent : maintenant c’est nous qui allons décider de ce que nous voulons, et nous allons nous reconnecter à notre propre puissance intérieure.

How to break free from everything projected onto us, how do we reclaim a way of being a woman, feminist, human on earth. And besides, it concerns men just as much. The underlying topic is rather how each man and woman cultivates within them both the masculine and feminine principles and how they come together in love. That’s why it concerns both men and women. How will I as a woman cultivate my masculine principle in order to better welcome the feminine principle?

You are finishing a second novel, is it also written from an ecological perspective?

I don’t really have a message in my novels, and that’s what’s liberating, compared to essay writing, which is more cerebral and didactic. The novel is written with the heart and with the body. You are truly in freedom and nuance. You can also campaign against yourself, with the diverse speeches of your characters.

But it’s true that I can’t help but set up scenes and raise questions related to ecology.

What are your upcoming projects?

I’ve started another project, which are fragments, it’s a project more linked with poetry and that I’ve called “Greeneries”. This month, a great collective book on autonomy, to which I contributed, is also being released by Rustica, in the “work autonomy” section.

And I want to write a book on sex and love. It’s a big subject, I want to handle it well, take the time, go and collect testimonies!

Portrait © Matthieu Brillard